Following the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, POTUS FDR asked Congress for a U S declaration of war.

In 2001 and 2002, George W. Bush sought and received congressional authorization before invading Afghanistan and Iraq. Those presidents followed the Constitution’s plain instruction: The power to take the nation from peace to war belongs to Congress.

So why, today, does the United States repeatedly engage in hostilities without a vote, a debate, or meaningful public consent?

The answer is not confusion in the law. The Constitution is unambiguous. Article I gives Congress the power “to declare War.” Article II makes the president commander in chief of the armed forces—but only after war has been authorized. The framers debated this at length. They had no interest in vesting the most consequential decision a republic can make in the hands of one person.

What has changed is not the law, but the behavior of institutions charged with upholding it.

The modern breakdown began in Korea. In 1950, President Harry Truman sent U.S. troops to fight on the Korean Peninsula without seeking a declaration of war, calling it a “police action” conducted under United Nations authority. Congress acquiesced. Nearly 37,000 Americans died. The precedent stuck.

From that moment forward, presidents learned they could initiate military action first and ask constitutional questions later—or not at all. The Cold War accelerated this shift. Nuclear weapons, global military commitments, and a culture of permanent emergency created a rationale for speed over deliberation. Congress accepted the premise that debate was a luxury the modern world could not afford.

Vietnam should have been the corrective. Instead, it produced a half-measure. The War Powers Resolution of 1973 was intended to restrain unilateral presidential war-making by requiring notification and withdrawal absent congressional approval. Presidents of both parties have treated it as advisory, not binding.

Then came Sept. 11.

In the emotional aftermath of the attacks, Congress passed the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force. It authorized force against those responsible for 9/11 and those who harbored them. It did not name countries. It did not define an endpoint. It did not anticipate drone warfare, cyber operations, or militant groups that did not yet exist.

That single vote has since been used to justify military action in dozens of countries, across multiple administrations, against enemies only loosely connected—if at all—to the original attacks. The 2002 Iraq AUMF, similarly outdated, remains on the books more than two decades later.

These authorizations became constitutional camouflage: not declarations of war, but permission slips broad enough to cover almost anything.

Congress bears primary responsibility for this state of affairs. War votes are politically risky. They force lawmakers to own outcomes—casualties, instability, failure. It is far easier to let presidents act than criticize or applaud from a safe distance. Abdication has become a bipartisan habit.

The public, meanwhile, has been excluded from the process. FDR understood that legitimacy required consent. Even Bush, in the charged atmosphere after 9/11, sought formal approval. Today, Americans often learn their country is at war after missiles have already been fired, the action framed as limited, defensive, or already concluded.

This is how a constitutional republic drifts toward an imperial presidency—not through a coup, but through erosion. Powers unused are powers lost. Silence becomes assent.

None of this is inevitable. Congress can repeal outdated authorizations. It can insist on votes before hostilities. It can reclaim the authority the Constitution explicitly grants it. What has been lacking is not legal clarity, but institutional courage.

There needs to be a discussion of the extraterritorial activities of Venezuela’s SEBIN or Cuba’s G2 intelligence agency. Leaders rightly raise concerns about the human rights of the civilians targeted by the U.S. airstrikes, but they say far less about the human rights of Cubans, Nicaraguans, Salvadorans, and Venezuelans suffering government repression .

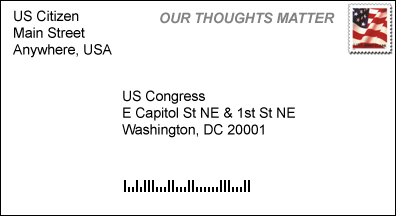

The question to be answered about our government is whether a Republican-controlled Congress is willing to fulfill its job, and if Americans will demand that it do so before the next war begins without a vote.