Do you recall the good old days when members of the Republican Party were also famous leaders who made us want to think?

Although I have no political affiliation, I was recruited to work as a G-15/10 for the Reagan-Bush Republican tag team. The Grand Old Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States. The GOP was founded in 1854 by anti-slavery activists who opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed for the potential expansion of chattel slavery into the western territories.

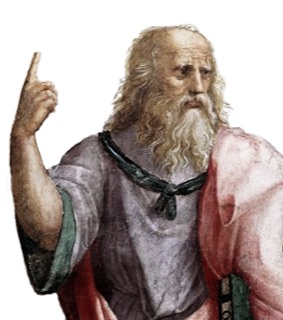

But who was the first Republican? Plato was allegedly the fitst. He reportedly said human beings live in their own world. Everything is an appearance.

In his ideal Republic, there would be no marriage except among the poor. Children would be removed from their parents and educated by the state. Ros is regarded as the soul impulse, the lowest form to produce a beautiful person.

Many people associate Plato with a few central doctrines that are advocated in his writings: The world that appears to our senses is in some way defective and filled with error, but there is a more accurate and perfect realm populated by entities (called "forms" or "ideas") that are eternal, changeless, and in some sense paradigmatic for the structure and character of the world presented to our minds. he most critical abstract objects are now called because they are not located in space or time) are goodness, beauty, equality, bigness, likeness, unity, being, sameness, difference, change, and changelessness. These terms—"goodness," "beauty," and so on—are often capitalized by those who write about Plato to call attention to their exalted status, similarly for "Forms" and "Ideas.”) The most fundamental distinction in Plato's philosophy is between the many observable objects that appear beautiful (good, unified, equal, oversized) and the one entity that is what beauty (goodness, justice, unity) is, from which those many beautiful (good, unified, equal, big) things receive their names and their corresponding characteristics. In some way, Plato's primary work is devoted to or dependent on this distinction.

Another feature of Plato's writings makes him distinctive among the great philosophers and colors our experience of him as an author. Nearly everything he wrote takes the form of a dialogue. The re is one striking exception: his Apology, which purports to be the speech that Socrates gave in his defense—the Greek word apologia means "defense"—when, in 399, he was legally charged and convicted of the crime of impiety. Ho ever, even there, Socrates is presented at one point, addressing questions of a philosophical character to his accuser, Meletus, and responding to them. In addition, since antiquity, a collection of 13 letters has been included among his collected works. St ll, their authenticity as compositions of Plato is not universally accepted among scholars, and many or most of them are almost certainly not his (see Burnyeat and Frede 2015. Most of them purported to be the outcome of his involvement in the politics of Syracuse, a heavily populated Greek city in Sicily ruled by tyrants.

We are familiar with the dialogue form through our acquaintance with the literary genre of drama. But Plato's dialogues do not try to create a fictional world to tell a story, as many literary dramas do, nor do they invoke an earlier mythical realm, like the creations of the great Greek tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Nor are they all presented as a drama: in many of them, a single speaker narrates events in which he participated. They are philosophical discussions—"debates" would, in some cases, also be an appropriate word—among a small number of interlocutors, many of whom can be identified as actual historical figures (see Nails 2002, and often they begin with a depiction of the setting of the discussion—a visit to a prison, a wealthy man's house, a celebration over drinks, a religious festival, a visit to the gymnasium, a stroll outside the city's wall, a long walk on a hot day. They form vivid portraits of a social world as a group and are not purely intellectual exchanges between characterless and socially unmarked speakers. At any rate, that is true of many of Plato's interlocutors.

Then in 1858, Abe Lincoln ran against Stephen A. Douglas for Senator. He lost the election but gained a national reputation for debating with Douglas, winning him the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. As President, he built the Republican Party into a strong national organization.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/abraham-lin….

Then there were the three RRRs. Al o a member of the Republican Party, he previously served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 to 1975 and as President of the Screen Actors Guild from 1947 to 1952 and from 1959 until 1960. Tampico, Illinois, U.S. Los Angeles, California, U.S.

Freedom is fragile, and it's never to see more than one generation away from extinction. It is not ours by way of inheritance; it must be fought for and defended constantly by each generation, for it comes only once to a people. And those in world history who have known freedom and then lost it have never known it again.

Knowing this, it's hard to explain those among us who, even today, would question the people for self-government. I've ofteI'veedered if they will answer those who subscribe to that philosophy. If o one among us is capable of governing himself, then who among us can manage someone else?

https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/ronald-reag…