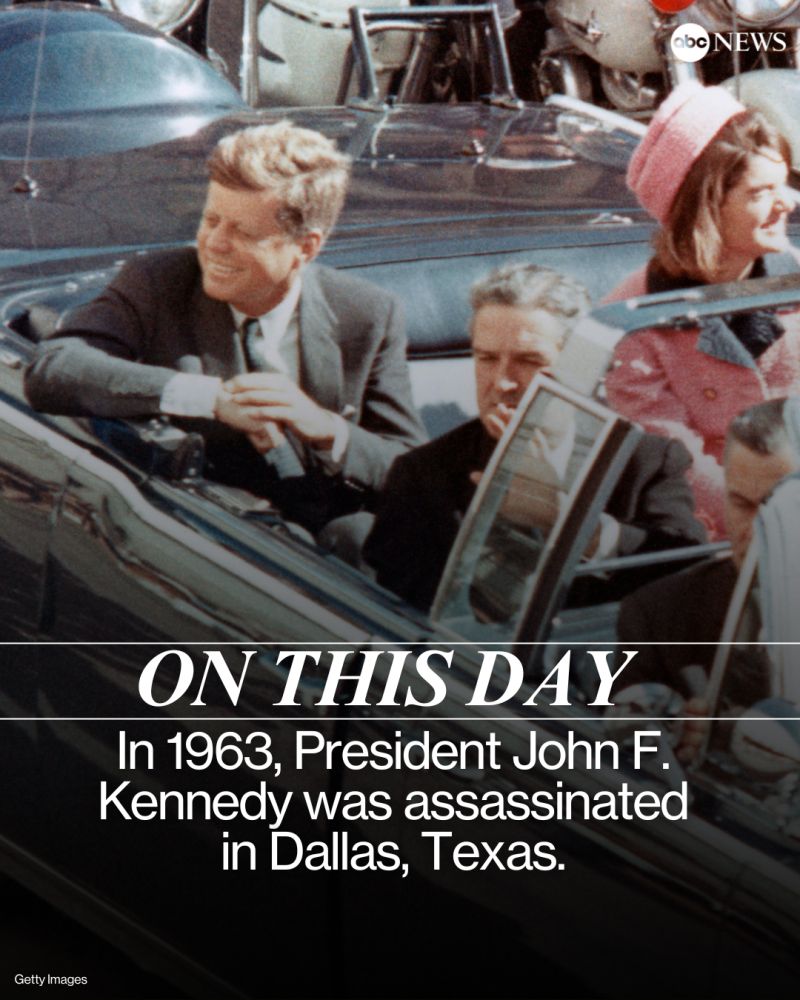

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas Texas.

JFK's assassination is remembered 60 years later by surviving witnesses to history, including AP reporter

Some of the last surviving witnesses to the events surrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy are among those sharing their stories as the nation marks the 60th anniversary

https://apnews.com/article/jfk-assassination-anniversary-ap-peggy-simps…

Dwindling witnesses to JFK assassination keep story alive 60 years later

https://www.upi.com/Top_News/US/2023/11/22/jfk-assassination-60th-anniv…

According to Wiki published reports, the Eisenhower administration had created a plan to overthrow Fidel Castro's regime through an invasion of Cuba by a counter-revolutionary insurgency composed of U.S.-trained, anti-Castro Cuban exiles led by CIA paramilitary officers. Kennedy had campaigned on a hardline stance against Castro, and when presented with the plan that had been developed under the Eisenhower administration, he enthusiastically adopted it regardless of the risk of inflaming tensions with the Soviet Union. Kennedy approved the final invasion plan on April 4, 1961.

On April 15, 1961, eight CIA-supplied B-26 bombers left Nicaragua to bomb Cuban airfields. The bombers missed many of their targets and left most of Castro's air force intact. On April 17, the 1,500 U.S.-trained Cuban exile invasion force, known as Brigade 2506, landed on the beach at Playa Girón in the Bay of Pigs and immediately came under heavy fire. The goal was to spark a widespread popular uprising against Castro, but no such uprising occurred. No U.S. air support was provided. The invading force was defeated within three days by the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces; 114 were killed and over 1,100 were taken prisoner. Kennedy was forced to negotiate for the release of the 1,189 survivors. After twenty months, Cuba released the captured exiles in exchange for a ransom of $53 million worth of food and medicine. The incident made Castro feel wary of the U.S. and led him to believe that another invasion would take place.

Biographer Richard Reeves said that Kennedy focused primarily on the political repercussions of the plan rather than military considerations. When it proved unsuccessful, he was convinced that the plan was a setup to make him look bad. He took responsibility for the failure, saying, "We got a big kick in the leg and we deserved it. But maybe we'll learn something from it." He appointed Robert Kennedy to help lead a committee to examine the causes of the failure. The Kennedy administration banned all Cuban imports and convinced the Organization of American States to expel Cuba.

In late 1961, the White House formed the Special Group (Augmented), headed by Robert Kennedy and including Edward Lansdale, Secretary Robert McNamara, and others. The group's objective—to overthrow Castro via espionage, sabotage, and other covert tactics—was never pursued. In November 1961, he authorized Operation Mongoose (also known as the Cuban Project). In March 1962, Kennedy rejected Operation Northwoods, proposals for false flag attacks against American military and civilian targets, and blamed them on the Cuban government to gain approval for a war against Cuba. However, the administration continued to plan for an invasion of Cuba in the summer of 1962.

In the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Khrushchev increased economic and military assistance to Cuba. The Soviet Union planned to allocate in Cuba 49 medium-range ballistic missiles, 32 intermediate-range ballistic missiles, 49 light Il-28 bombers, and about 100 tactical nuclear weapons. The Kennedy administration viewed the growing Cuba-Soviet alliance with alarm, fearing that it could eventually pose a threat to the United States. On October 14, 1962, CIA U-2 spy planes took photographs of the Soviets' construction of intermediate-range ballistic missile sites in Cuba. The photos were shown to Kennedy on October 16; a consensus was reached that the missiles were offensive and thus posed an immediate nuclear threat.

Kennedy faced a dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites, it might lead to nuclear war with the Soviet Union, but if the U.S. did nothing, it would be faced with the increased threat from close-range nuclear weapons (positioned approximately 90 mi (140 km) away from the Florida coast). The U.S. would also appear to the world as less committed to the defense of the Western Hemisphere. On a personal level, Kennedy needed to show resolve in reaction to Khrushchev, especially after the Vienna summit. To deal with the crisis, he formed an ad hoc body of key advisers, later known as EXCOMM, that met secretly between October 16 and 28.

More than a third of U.S. National Security Council (NSC) members favored an unannounced air assault on the missile sites, but for some of them this conjured up an image of "Pearl Harbor in reverse." There was also some concern from the international community (asked in confidence), that the assault plan was an overreaction because Eisenhower had placed PGM-19 Jupiter missiles in Italy and Turkey in 1958. It also could not be assured that the assault would be 100% effective. In concurrence with a majority vote of the NSC, Kennedy decided on a naval blockade (or "quarantine"). On October 22, after privately informing the cabinet and leading members of Congress about the situation, Kennedy announced on national television the naval blockade and warned that U.S. forces would seize "offensive weapons and associated materiel" that Soviet vessels might attempt to deliver to Cuba.

The U.S. Navy would stop and inspect all Soviet ships arriving off Cuba, beginning October 24. Several Soviet ships approached the blockade line, but they stopped or reversed course to avoid the blockade. The Organization of American States gave unanimous support to the removal of the missiles. Kennedy exchanged two sets of letters with Khrushchev, to no avail. United Nations (UN) Secretary General U Thant requested both parties to reverse their decisions and enter a cooling-off period. Khrushchev agreed, but Kennedy did not. Kennedy managed to preserve restraint when a Soviet missile unauthorizedly downed a U.S. Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft over Cuba, killing the pilot Rudolf Anderson.

At the president's direction, Robert Kennedy privately informed Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin that the U.S. would remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey "within a short time after this crisis was over." On October 28, Khrushchev agreed to dismantle the missile sites, subject to UN inspections. The U.S. publicly promised never to invade Cuba and privately agreed to remove its Jupiter missiles from Italy and Turkey, which were by then obsolete and had been supplanted by submarines equipped with UGM-27 Polaris missiles.

This crisis brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any point before or after. It is considered that "the humanity" of both Khrushchev and Kennedy prevailed. The crisis improved the image of American willpower and the president's credibility. Kennedy's approval rating increased from 66% to 77% immediately thereafter.